From a pop-up restaurant at Base Camp, Mt. Everest, Joseph Lidgerwood has already had a big impact. But far away from the logistical conundrum that must have been, he presides now over peace and tranquility.

At Restaurant Evett, in Seoul, South Korea, the locals dine early.

And this is Michelin dining. In that rarefied air of high end, very expensive fine food, where the dishes are as much about theatre as the Bolshoi Ballet, guests don’t want to be rushed. Joseph Lidgerwood, the chef/owner, won his Michelin star in the first twelve months of operations. Astounding, and unusual.

So at Restaurant Evett, how does an evening roll out?

“Doors open at 6pm, and with 15 or 16 courses, a dinner at Restaurant Evett lasts a long time,” advises Joseph. He has tried two sittings, but the guests at this restaurant like to linger, so it’s usually one sitting and how many guests? 15 or 19 at a push. Wow! That’s boutique.

Joseph estimates the standard length of a dinner is 150 – 170 minutes, and with no choice in the food menu – the waiters just take the beverage orders with three beverage pairings, it’s hard to imagine a more streamlined service.

“The first snacks come out from the kitchen pretty quickly. The service itself, from where I’ve worked before, is a lot calmer. It’s very quiet, not much needs to be said, and it’s an open kitchen and it just flows.”

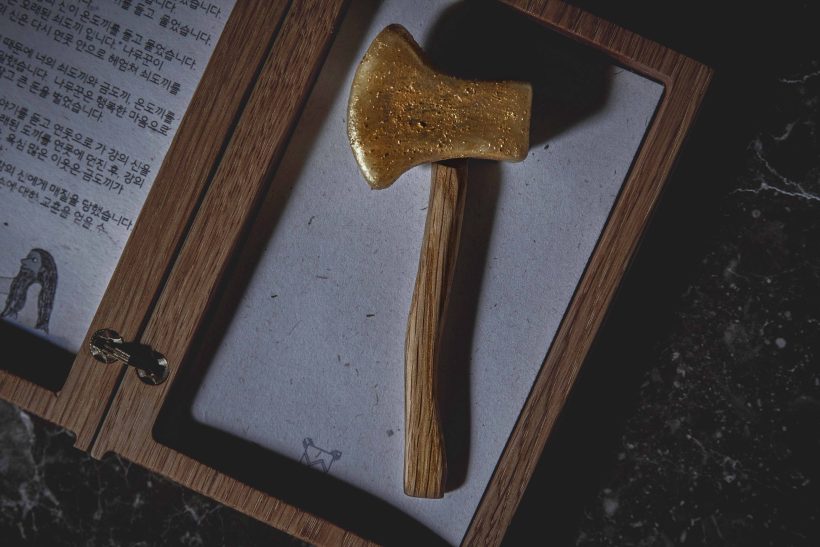

Entrée at Restaurant Evett

How big is the brigade?

“It kind of fluctuates. We have a lot of interns, but we normally have 10 chefs for 15 guests.”

Hold the phone! What? Almost one chef for every guest?

“Seems a bit outrageous I know, but it’s kind of the food style that we do. The chefs also serve so we have two front of house and then normally on a service we have 7-8 chefs depending on where I’m positioned. But though we open at 6pm the first chefs start at about 5.30am so the actual working day is a wide spread. There’s a lot of detail in the food we do here.

“Why? It’s because there’s two types of food or cooking that I like to eat. Very well prepared, thoughtful food or it’s super simple, and delicious. What we like to do is the incredibly creative, thought provoking unique experience of fine dining. That people enjoy maybe once a year, special occasion. I love having the space to create very delicious, unusual flavours that spark a fantastic dining experience.

Restaurant Evett, with Joseph Lidgerwood, now Michelin Chef in his own restaurant in Seoul Korea. Far away from his beginnings in Kingston, Hobart, Tasmania.

“That’s an area that’s getting harder and harder to enjoy around the world, so trying to make something that’s a destination not just for guests, but also the service staff. Anyone with ambition now wants to work somewhere that’s creative, and not just a place that pumps out classic well-known dishes.

“We’ve done a lot of events lately. We did one down south in an amazing jang field, where they make the Kim Chi and all other Korean ferments like Gochujang and Doenjang.”

Ants? Yes, why not?

How did all this passion start?

“I got into cooking really haphazardly. I didn’t want a job sitting down, I’ve got too much energy, and I wasn’t very good at studying. Ha! I went to college and failed cooking! I was the only person in class who got ‘not competent’ and I’m the only one still cooking.

“I left after year 11 and got an apprenticeship at a restaurant in Huonville, then the Astor Grill, back in the day. Then Industry Link and finally at Henry Jones, with a couple of good chefs who pushed me. Tasmania wasn’t the foodie capital then that it is now. So I went to London, worked at a couple of Michelin restaurants there, bounced back to Australia, then Tom Aikens, a chef I knew from the UK opened in Hong Kong and I helped with that.

“Ever curious and looking for new challenges, I turned 25 back in London, working at The Ledbury, under another Australian chef, Brett Graham, with two Michelin stars and high stakes. But I headed to burn out. Before you even start in many of the world’s top restaurants, they make you sign a piece of paper that working more than 48 hours is fine with me, and trust me, it’s usually much more than that! Try 95.

“It’s kind of a double edged sword, you can become a good chef by working those long hours, learning, doing, but burn out is common. And the price you pay. At The Ledbury, you could tell if new staff were going to make it, based on how far from the restaurant they lived! If they lived further than 20 minutes way, it would go like this: ‘How far from the restaurant do you live?’ And if they answered, ‘Oh, thirty, or 45 minutes…” You would instantly know they’d be gone in three to four weeks.

A dessert: Art is on the table

“Every day started at 6.30, 6.45am, and service/work would finish at 1am, then you’d be back up to work that same day, so 4 hours sleep is the most you would get. I got a bit jaded with the London grind. After 7 years, my friend who was working at Noma was feeling burnt out. (For clarity, Noma was voted No. 1 of the top 50 best restaurants in the world in 2021 and continues to push the boundaries of foraged ingredients and wild food combinations. It’s a wonder the chefs don’t eventually self-immolate, as the pressure is always on).

“My friend and his friend, who wasn’t a chef and his wife who was a restaurant manager, we all banded together and formed a restaurant group called One Star House Party, and we started in New York, and my friend James raised some money. We travelled from city to city and opened up pop-up restaurants, got picked up by Eater Magazine, and moved from there to doing a pop up restaurant at Base Camp, Mt. Everest, and one in a train from Hanoi to Sapa, Taiwan, one in Oman.

“The pop up experience at Base Camp Everest was one of the hardest and most rewarding pop ups I ever did. It was the biggest challenge as the physical aspect of just doing the walk let alone preparing a pop up was extremely taxing on my body. I would probably never want to do one that demanding again but in the same token I am very proud I was able to accomplish it. Fond memories to come.

Below is a small video from the team that travelled to Nepal for the trip.

“I came to Korea as one of the pop ups, and not many people knew much about Korean cuisine, and I became interested, and one of the pop ups offered me the premises here. My wife is Korean and we own half each. For me, it was a different cuisine, an exploration, which excited me.

“Being here is a steep learning curve, with vastly different ingredients. The final restaurant in the USA I worked in at 28 was The French Laundry, in California, which was a kind of finishing school thanks to Tom Aiken with whom I worked in the UK. I faced a turning point in my career. The bar was high – constant curve balls, problems to solve, where there’s no real room for failure. A meal with wine pairing, is over a thousand dollars, and 120 guests per night. The expectation is massive. I was offered to stay on as sous chef, but I was also offered to come to Korea.

“To explain the difference, in The French Laundry, which is so established, it is systematic, and great for someone who wants to cook at that level, but not a lot of room for invention, for freedom. It’s organised to the last degree, but unless you move through the sections, then it can get repetitive and there’s very little responsibility. It’s a huge beautiful organisation, but limits the learning, the invention. There’s no real room for failure, but the system supports that. I felt that to own my own restaurant and make mistakes and create, invent, was more important.

“I understand now more of what the market here want, expect, and need. At the start it was tricky. 35% – 80% of our clientele are Korean, so the sourness level I had to drop completely. The acidity using lemon etc. was different, and it was hard to get the actual deep needs of seasoning. Using a lot more fermented products to arrive at the flavour palate was crucial and grounding some of the dishes in the familiar to explore difference. Having a certain aspect in the familiar realm is important that our customers can happily try something different and enjoy.

Dessert

“At the moment we make a kombucha from sesame leaf, it’s super acidic and sharp, but because they understand the flavour of a parilla leaf they understand the flavour and enjoy it.

“We use a lot more seaweed to arrive at salinity, as opposed to raw salt, and fermented cabbage or radish juice to arrive at acidity. It’s kinda good to force yourself out of the comfort zone. I didn’t want to do fusion – for me it just doesn’t work.

“I just wanted to drive the ingredients into a new area, what else it can be. I’m not limited by being a Korean chef, so I don’t have that same limitation. The research has been huge. And the expectation to do fine dining limited by certain traditional dishes just doesn’t appeal to me. So I push the envelope, but it’s still Korean.

“I’ve been open for 3 and a half years, 2 years under Covid – we closed for a month in March, 2020, but on the whole, with lockdown it was tough. We were still open and trading, but no one would come. We were fully booked after getting our first star, and then Covid hit. Zeros. Delivery wasn’t a thing, and we used to do private dining but it was hard.

“We’ve done a renovation recently, because I felt after 3 years, debt free we refurbished and changed layout completely, and we’re pushing for another star this year. We had 7 tables plus bar, now just 5, and from 26-18 it’s now 16-18 guests.

“Now? We’re looking at opening a more casual restaurant with Australian ingredients. A grill perhaps, a simpler approach hopefully by early next year. Diversifying is the key I think, to explore different markets. There’s massive interest here in Australian ingredients. And I’m developing a drink range that’s based on Korean ingredients, but is different. I designed the label, based on the Korean hat. We did a Tasmanian pepper berry spiced drink, and I made a quince chong using the syrup, last year we used magnolias, it’s all been insanely well received. The Australian Embassy here is stocking it so I’m hoping the new Australian style restaurant is as well received.”

Joseph seems so cool and calm for a Michelin chef, with a brigade to organise and a bar that’s so high, most restaurants never reach it. His inventiveness and enthusiasm for new ideas pushes him along a road few reach.

If you travel to Seoul, make sure you book ahead.

Christine Matheson Green 🙂