Henry Anderson has what seemed to me an unusual job. Marine Catering.

I was interested – exactly what is marine catering? He consults on big ships, bringing their kitchens (i.e. galleys) into shape and training their staff to deliver amazing quality food to ship’s officers and crew on time, and on budget, in line with best practice. The challenges, at times, are enormous, but Henry delivers, time after time.

This is his story:

How did you start in hospitality? What were the drivers?

“When I stayed at my grandmother’s house as a young boy I would watch her chopping vegetables to make soups and stews and she would let me help with the preparation. Food has always interested me as long as I can remember and it was a natural progression for me to learn how to cook and create dishes that people would enjoy to eat. In the highlands people cooked what they had, ham hocks, dumplings, standard things people would make in Aberdeenshire.”

Describe your journey briefly, some mentors or people who inspired you and influenced you?

“Growing up, my father worked as a trawl fisherman and would take me with him from the age of eight years old. It was an expectation on his part that I would become a fisherman like him but I wanted to be a Chef so I financed my catering course at Aberdeen college with the money I earned from fishing during the holidays.

I was inspired mainly while at college by Michel and Albert Roux and their work at La Gavroche in London, the first restaurant in the UK to win a Michelin star. “

How did you end up in the particular segment of the industry you are in now?

“I’m Scottish and I was located in Aberdeen, ‘the oil capital of Europe’, where there was plenty of work for chefs on the North Sea oilrigs and tankers. I joined a large international catering agency – and worked gaining experience in big catering establishments in the UK, in remote sites in many countries and on board large merchant vessels in the oil and gas industry. The Company took me from a unit in Aberdeen and sent me to Singapore where I made major changes on board the fleet of vessels I was assigned to. Everything necessary was achieved and completed. Back off that I was placed on oilrigs catering for large numbers of crew. I In 2004 I saw an opportunity and started my own offshore Company. It was a risky thing to do – to start an offshore company, as the industry is very transient, but I’d developed a reputation for delivering on time and to the client’s budget through the implementation of my training programs, and my Company is recognised for achieving high standards in the catering section of the industry.”

What are some of the big and small challenges you face on assignment?

What are some of the big and small challenges you face on assignment?

“I would say that controlling budgets in regard to menu structure and cost control is a big challenge. Also, environmental factors, that can affect the working conditions on the vessels at sea, such as cyclones, can make working conditions difficult on board. And so often you’ve no idea who you’re meeting until you get on the ship. From a captain’s point of view things can be very different to what’s happening in the galley. Through experience I now can see in a millisecond who can, who will and who won’t do the job.

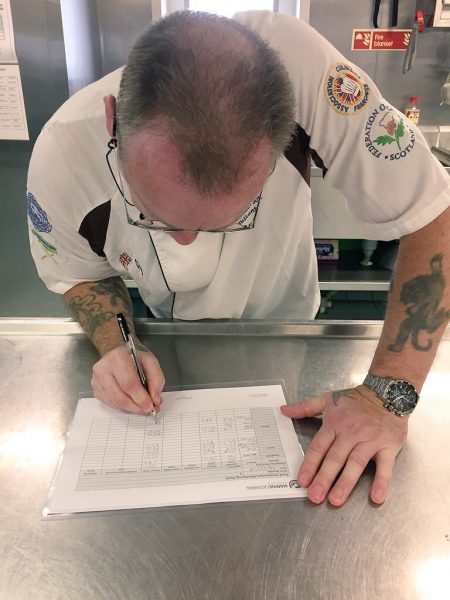

I have to put a project into place that will make common ground, and leave a finished product that suits my client’s requirements in regard to, health and hygiene and standard culinary services in line with ILO MLC regulations. The entire experience is what I have to cover – teaching people to multi-task is a big part of my day. It’s all about teaching them, demonstrating the job and working side by side.

If you were to take a chef out of a normal kitchen and put them in to do my job they would have difficulty in putting a system in place within the limited timeline. To educate the catering team to a position where they can maintain that system, unsupervised, for the duration of their time on board the vessel, is huge, while achieving the standard required to run a successful catering department and comply with regulations on an ongoing basis. It’s not just about cooking well or even leading a team. The pressure of time is enormous.”

What have you found is the key?

What have you found is the key?

“I need to find out the weaknesses of people in the catering departments and build from there – that’s where coaching and development comes into its own. People cover up and hide behind their egos, so I need to look past that glass plate and see the people I’m dealing with. If they’re highly stressed, then I need to see that and adjust accordingly. I have to blend and become one of the team so that they are comfortable, and know I’m not lording over them. I just have to show them what to do.”

What’s the biggest hurdle you face in every assignment?

“I can be 40 hours or more without sleep just getting to a vessel. So I am quite tired when I get there, meet the captain, the staff and start with the training. I have to make every second count and I’m working 12-hour shifts. I normally have a maximum of 14 days on board to make huge changes, and it takes 2 days to write the reports and table those to the staff and captain. Then I have to give the staff an appraisal and development plan, which lets them see what they’ve achieved during training and they’re left with a schematic development plan to work to until my next visit.”

Wow! That’s enormous. Can you break that down?

Wow! That’s enormous. Can you break that down?

“They get a Standard of Practice manual to make sure they’re complying to industry standards, and on hard drive a system they can check in with. On every ship, I have to create a 5week menu cycle, with recipes to suit, and there are 30 items on the menu for people to choose from every day. Plus I teach a salad bar matrix – 20 salads to choose from every day. I make sure that healthy options are always available. Plus, I teach them to make breads, desserts, patisserie etc. which all has to be costed to budget. And I always have to cater for many nationalities, and levels of English and communication.”

Communication is key, isn’t it?

(Henry laughs long and hard here).”I’ve no time for malingerers Have you ever heard of flat foot, where you kick arse so hard your foot goes flat? Well,. that may have been the practice onboard ships in olden times but I am happy to say I don’t do that to my trainees! There may be a language barrier that could be taken for intransigence. But I’ve found that within a day understanding can be reached and humour is a great thing to take the sting out of any awkward moments as nobody wants flat foot!”

Your biggest issue then?

Your biggest issue then?

“ When they know that they are going to have training, catering crews can get frightened. Our job is to take the fear out of the job – see the weaknesses, pull them out and give them work that they can do and build their strengths and motivation.” When I get on a ship, people think I’ve got a magic wand. I tell them don’t use these words, maybe, but, or because– they’re commonly words used as the start of an excuse. And for me, there is no room for excuses, only solutions.

The main thing I try to do is to train their brains a different way, to see solutions, not problems, and you’ll get a different person. You need to be on the cliff face with people every moment you’re with them. Observing every minute of the day. You’ve seen the weaknesses. You’ve got to nullify them. I start with the chief cook and a hotplate, and make my way round the 4 corners of the kitchen. I make sure I put a flow system in place.”

What are some of the changes you’d like to see develop?

“I would like shipping companies to recognise and understand how important it is for their staff to meet ILO/MLC requirements and standards within the catering industry, e.g. cooks to understand how important it is to use menu structure to comply with ships’ budgets.”

What would be your best advice to young people starting out? Is there anything you would change if you could, looking back?

“My advice to those starting out on their catering career is for them to be 100% serious about the job. To understand all that it entails and will be required of them, because it is a hard and demanding job and not for everybody. They should watch and learn whenever they get the opportunity from people skilled in the industry, learning the new trends and styles as they emerge. That way they will be prepared to step up to a higher position and make the transition with ease and positivity.

I have seen young trainee chefs facing difficulties within brigades in establishments and head chefs should be prepared to make allowances, and make allowances for people to join the trade. They should be moved around all areas of the kitchen not just to gain experience, but to be able to step in if there is a gap due to absence. Executive or Head chefs should not be above acting as mentors in this regard.

As a chef who strives for perfection in a competitive industry, I have enjoyed taking part in many Salon Culinaire events. I believe there is room for a school for mentoring chefs to this level, where they can come together and share their experience with new potential competitors.

As a chef who strives for perfection in a competitive industry, I have enjoyed taking part in many Salon Culinaire events. I believe there is room for a school for mentoring chefs to this level, where they can come together and share their experience with new potential competitors.

And my final tip? Always learn the job of the guy ahead of you, because that opportunity will come, and you need to be ready. During all the trials and challenges I pushed myself through, so you as a leader must pull your staff through. To do that you give them the right piece of the puzzle to succeed and get to the next level of enhancement. It just takes time.”

Henry finishes with a note about having worked in Australia, where he swears he’s never seen a bad chef, and saw a lot of good food. Really? I ask, amazed. Knowing full well that Australia has its share of disasters in the industry for much the same reasons as anywhere else. Henry though, is adamant, and one of the most positive chefs I’ve ever met. Perhaps that comes from managing a fresh-faced team on a rocking boat in a force 9 gale. That takes guts, and talent, and Henry’s got both, in spades.

Chrissie 🙂