Pierre Khodja had old-school chef training, but comes with a modern mindset. Michelin? Tick. Mentor? Tick.

What next? Not sure, but it’ll be interesting, that’s for sure. And Pierre, who brings the most massive skill set to any cooking job he does, will help shape the industry for years to come. Of that I’m sure.

Pierre and I first met at the 2017 Fonterra Proud to be a Chef launch, where as guest chefs we schmoozed and mingled with chef royalty in Melbourne. It was just after Jeremy Strode’s tragic and much publicised suicide, and Pierre took the mic after several others to highlight the difficulties of an industry in crisis.

His first words I’ll never forget:

“Being a chef is the loneliest job in the world…” and he went on to describe the disconnect between the pressure and madness of service, and families waiting at home for… what? A burnt out, empty shell, who had given his all to his work, and has nothing left over for the important things. For family, children, friends. Where’s the pleasure in that? Is there a better way? There must be, and now is the time for some soul searching that Pierre, like a beagle, is tracking the scent.

From his multi-cultural roots to the winding path that brought him to Australia, Pierre is a true chef of the world, and looks back to his childhood in Algeria that gave him his start, and love of food. No surprise the driver was his mother.

Pierre begins:

“My real love of food and cooking started with my mother, who was a great cook, in Algeria, and I still remember the smells of her food… When I was 7 we moved to Marseille, and then to Paris where I worked in kitchens. Mum taught me how to use cheap cuts and to do loaves and fish. She had eight kids and she saw it as her duty to feed us as well as she could, and our right to eat well at least. If we had nothing else, we always had full bellies.

She was incredible, she could make a feast out of nothing, and used every part of the animal. We loved the offal, and tasty dishes that she would make out of the cheapest, throw away cuts. Looking back, I don’t know how she did it, but we ate like kings, and the budget must have been tight.

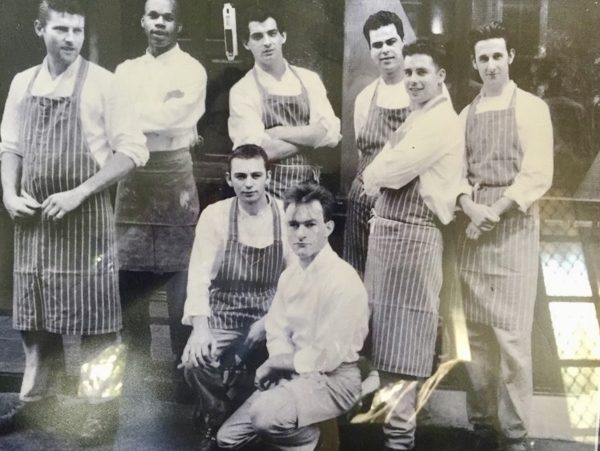

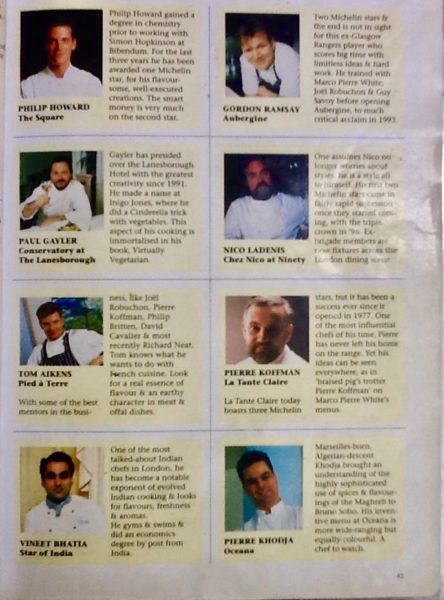

Back in those days, the 1970s, there was no apprenticeship like here. All the training was done in-house and we were taught onsite, and pretty soon I left Paris and went to London to work at Ma Cuisine, where I was a commis. It was a two Michelin star, with Chef Moullion and I said to myself I wanted to work in good places. I wasn’t after the money, I was after the knowledge. It was tough and relentless, but royalty ate there so for me, a young chef from Algeria? It was an exciting time.

I fell into a series of roles then, following the Michelin and the chefs who cooked to push the boundaries and to raise the standards of cuisine in England. I worked at St. Carlo which was a famous Italian restaurant in Highgate with 1 Michelin star as chef de partie. That also paraded a who’s who in the zoo of customers, from royalty down who went to be seen and stayed for the food. Then, at the Royal Garden Hotel which held 1 star and following that, the Roof Kitchen in Kensington where I became a senior Chef de Partie and I ended up in Enoteca for about a year.

I fell into a series of roles then, following the Michelin and the chefs who cooked to push the boundaries and to raise the standards of cuisine in England. I worked at St. Carlo which was a famous Italian restaurant in Highgate with 1 Michelin star as chef de partie. That also paraded a who’s who in the zoo of customers, from royalty down who went to be seen and stayed for the food. Then, at the Royal Garden Hotel which held 1 star and following that, the Roof Kitchen in Kensington where I became a senior Chef de Partie and I ended up in Enoteca for about a year.

I was getting known around the town and in dining circles, and I finally went to open my own place in Hampstead. The way it played out usually, was the wealthy lawyers and accountants, who offered to back you slowly, slowly watched, waited, and finally came out to have a drink. Then they would decide you were someone who had a following, who was cutting edge, and could create a buzz. Marco went on the same trajectory.

I had the offer of backers, and I decided that Base was the name and Hampstead was the centre of the food universe in London at the time. I was head chef for 2.5 years, but my lease finished, and I wanted more knowledge. It’s interesting, the pressure to invent is so intense when you run your own restaurant, but without a huge background and knowledge, you can get sucked dry, so I decided to move to Bistro Bruno.

It was a risk, but the chef was Bruno Loubet, and he had a red M before Michelin stars existed, with 4 rosettes, and an Aros award from the Evening Standard. He was my idol, and he took me on as his sous chef. For me, it was an amazing education. We worked with whole beasts from huge cows to suckling pigs and broke them down, working with the structure of the animal, and using every part. Nothing was allowed to be wasted.

It was a complete scratch kitchen and I learnt butchery, patisserie, and upgraded my skills in a better way. Grant King from The Pier in Sydney worked with me there.

Bruno was my mentor and he was one of the best chefs I worked with for a long time. We’re still good friends – he loved spices, I loved spices too. It goes back to my time in Algeria… In Andalucia, the Arabs would travel and plant their spices; when they grew, they’d give it to the animal first and if it survived they used it and experimented.

From Bruno I went to Oceania in London with Gary Holyhead who had 1 star and he’d worked for Marco. But, as things happen, he left and I took over as head chef. I was there for two and a half years, and went on holiday to Tunisia, where I met a guy whose wife was from Melbourne. That set us on a move to Australia, and together we opened a restaurant in Mornington and called it Albert Street Restaurant.

It was there I had a shocking accident (Pierre and an apprentice suffered horrific burns from a fireplace blast and were in hospital for a long time.) My friends from the industry stepped in to keep the restaurant going, and that just proves what an incredible brotherhood I have been lucky enough to be a part of. But, eventually I went back and got a hat and had it for 3 years. Then I sold and moved to Canvas in Hawthorn in 2006, where I had 3 hats for 3 years in a row.

The pressure of keeping that up is huge, and I needed a break, so I left and went to the Flinders Hotel back on the Mornington Peninsula, where I was for 5 years. There I was named Hotel Chef of the Year, and we were awarded a Chef’s Hat every year.

But the need to do my own thing is strong, so I left finally and opened my own place. I named it Camus after Albert Camus and we opened as North African with French roots. It’s been successful from day one and packed every night. I ran it with a brigade of 4 and 2 kitchen hands and we all worked together as a team. I demanded that we come back from 60 – 70 hours a week to now 50 hours maximum. Then we’re all running at top performance and have time to rest and recuperate. I know just how important that down time is.

I love the history and development of food. It’s such a part of us, as a species, our development and history, we evolved to survive and food was the driver. The first food was cooked on stone and early builders cooked meat on a hot brick, and now we’re going back to that with open fire pits and the heat of the kitchen being a part of the entire restaurant design – it satisfies a primal need I think.

I went to a meeting with Ferran Adrià (the godfather of molecular gastronomy and owner of the ground breaking El Bulli) at Essential Ingredient, who was asking us all questions about the origin of food, and I knew the answers because I know this stuff – customers see just the finished product. It takes a long time for any ingredient to grow – saffron takes a lot of work to grow and harvest. I want to educate them [the customers] more in this, and chefs too.

I went to a meeting with Ferran Adrià (the godfather of molecular gastronomy and owner of the ground breaking El Bulli) at Essential Ingredient, who was asking us all questions about the origin of food, and I knew the answers because I know this stuff – customers see just the finished product. It takes a long time for any ingredient to grow – saffron takes a lot of work to grow and harvest. I want to educate them [the customers] more in this, and chefs too.

For me as a chef and as a human being – simplicity is key. My grandfather and father ate simple food, well cooked. The food was clean and organic – we didn’t have to look for organic because it was a given – the land was so fertile. Food was cooked as fresh as possible, as simply as possible. And what mattered were the simplest of things – flavour, aroma.

We ate goat – did you know that it’s the only animal eaten by every religion? A farm that farms goats smells different to the farm that farms lamb. Even a piece of fish has its timing and you tell by the smell. And we still face these crazy fads – to the point that people now are scared of salt based on some research that’s been disproved anyway. It’s the blind leading the blind. If you haven’t eaten a good madeleine how can you know a good madeleine? That’s the issue. We need to go back to the roots, to where food was cooked with love and care, with knowledge and history is in every bite. That’s the magic.

In my kitchen, nothing comes in prepared, each animal has its own flavour – it’s what makes cooking so exciting. I teach my apprentices everything from stock upwards – it’s my duty to pass all my knowledge to my youngsters before I go or the industry will die.

You have a responsibility to teach them, to help them, to respect them. Now, youngsters come in with low self-esteem. Isn’t that a tragedy in itself? In Europe, being a chef is a career, it’s a choice, here it’s a last resort – you see them walking in the street in filthy uniforms. That breaks my heart.

I have high standards – my kids have to be clean and have the right attitude. People learn better by watching than by listening – hands on next to you.

I teach them the business side as well. That is so important, to teach the costs, how to deal with suppliers, everything. When we buy fresh food there’s no GST but when we sell it, there is GST … so many chefs don’t learn the business side. Even if you are a commis or sous, you have to be a businessman now and understand all the hidden costs, so you’re all on the same page. Some restaurants put the costs of running a restaurant on a big piece of paper in the kitchen for all to see. That’s a big reminder that everything, even the water, in a kitchen costs money.

I teach them the business side as well. That is so important, to teach the costs, how to deal with suppliers, everything. When we buy fresh food there’s no GST but when we sell it, there is GST … so many chefs don’t learn the business side. Even if you are a commis or sous, you have to be a businessman now and understand all the hidden costs, so you’re all on the same page. Some restaurants put the costs of running a restaurant on a big piece of paper in the kitchen for all to see. That’s a big reminder that everything, even the water, in a kitchen costs money.

For farmers it’s a race against nature. They get up early, and finish late. Even to produce potatoes, it’s a huge undertaking, and the humble onion takes a long time to grow. What I’m trying to say is that the entire paddock to plate pathway is a massive, complex, difficult intermingling of hundreds of dedicated and hardworking people who risk everything to bring that perfect dish on a plate that’s in front of you. So if you want to complain about the price? Get out.

Our young chefs need guidance and protection, knowledge from hygiene to food rules to all the tiny parts that make up a service in the back of house. And collaboration is all – you can’t clap with one hand! You need both hands to clap and you’re artists – it’s about love, countries, nationalities, farmers – you pull it all together to put that on a plate.

Food has been an integral part of our culture since the old days. Think about it – people come and do million dollar deals over a meal, big things happen on a table! Bank managers get wined and dined – it’s a serious thing, it’s not a joke – cooking is not about tattoos and tweezers – it’s about knowledge, timing, farming and slow – we all rush too much.

I do feel now though that customers need to be educated, and quickly, because this industry is like a runaway train. Where I come from a chef is a chef and a waiter is a waiter. Food is expensive, but these days, customers don’t want to pay. Working together to make a product is what it should be all about – hospitality – the very word comes from being hospitable. And over all? There’s a few people making a dollar but the rest are struggling.

My accident forced me to rest and recoup for months, so I had plenty of time to think about my life, what it all means, and what I’m here for. And that’s the most important thing. Now? My business is sold and all settled – I needed a break and I’m still looking for the right opportunity. But if I’ve learnt anything, that opportunity will appear at the right time, in its own way. Because that’s life, isn’t it?”

Aaaaah. And isn’t that the truth? Pierre has the wisdom of 9 lives, and perhaps that’s because he’s a survivor, and a deep thinker. He’s had forced time out that brought its own challenges but its own big lessons, and I for one will be grateful for the knowledge he’s shared with me, and now you. His opinions on food and the dining scene are erudite and thoughtful. Thank you, Pierre.

Chrissie ☺